Ramazan, the Muslim month of dawn-to-dusk fasting (also spelled Ramadan, Ramadhan, etc.), will begin at first light on March 23rd and end at sunset on April 21st 2023 (Since the Islamic calendar is lunar, the exact date will depend upon weather and the visibility of the new moon.)

Iftar: Breaking the Fast

Travelers to Turkey who want to experience the rich variety of the country’s cuisines are often concerned that they may find many markets and restaurants closed during Ramazan. They need not worry. On the contrary, the gastronomic scene in Turkey is even more vibrant, as observant Muslims break their fast with a variety of delicious foods, some of which are specific to Ramazan and rarely found outside Turkey.

The perfume of baking bread wafts through street markets filled with seasonal fruits, including dates from Mecca and other foods culturally significant to Muslims. Although some restaurants may be closed mid-day, all will be open and bustling after sunset. An array of Ramazan pastries, from savory böreks to the delicate, rose-scented dessert, güllaç, reward the faithful.

Nigella & sesame seeds on Ramazan pide

The only real inconveniences to anyone—Turk or visitor—are Ramazan’s colossal urban traffic jams. Residents rush home from work to appease their hunger and gather with families and friends to share the communal evening meal known as the iftar.

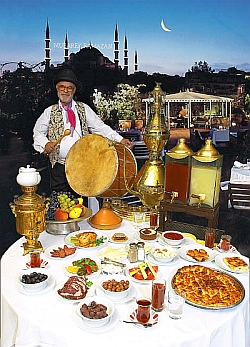

Feast for a Sultan

Indeed, the nights of Ramazan, traditionally filled with elaborate meals and public spectacles, are the most festive of the entire year. Imagine something akin to Carnival with Thanksgiving happening every night for a month… And when Ramazan falls during summer, the parties last long into the night. Occurring in the lengthening days of spring, as it does this year, will make the fasting longer, but the nights no less joyful. Nowhere is the atmosphere more exuberant than in Istanbul, with its many magnificent Ottoman imperial mosques. Domes and minarets illuminated against the dark adorn the sky throughout the month.

We are pleased to share with you two articles by Turkish historians that detail both the traditions and contemporary observance of Ramazan.

The first piece literally shines light upon the Istanbul custom of mahya, embellishing mosques with complex illuminations. The second study delves into the sophisticated culinary culture of the holy month. After reading these pieces, you’ll surely understand why Turks deem Ramazan to be “Sultan of all the months.”

by Necdet Sakaoğlu

Ramazan mahya

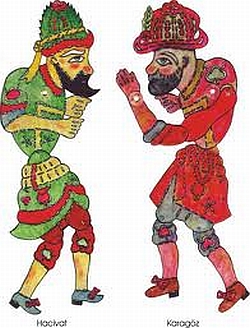

In Ottoman times the month of Ramazan was a festive time when people fasted and prayed by day, and after breaking their fast at dusk, enjoyed the sights and entertainments of Ramazan by night. Religious worship was combined with music, feasting, and performances of the Karagöz shadow play.

Hacivat & Karagöz Shadow-Puppets

Torch-lit parties in the tulip gardens and moonlit boat trips up the Bosphorus with songs and music were held when Ramazan fell in spring. Illuminations known as donanma sometimes took place on the Golden Horn or the Bosphorus, but Ramazan in Istanbul was above all symbolised by the mahya illuminations strung from the mosque minarets and lighting up the night sky in beautiful patterns.

Mahya illuminations were created by hundreds of tiny lamps hooked to ropes stretched between two minarets of a mosque in such a way as to write words of religious significance or to form pictures. This custom was based on the desire to express thanks to God for joy, abundance and prosperity, to encourage the populace to perform the good deeds appropriate to this holy month, and to instill in children a love of Ramazan.

Before the advent of electricity, preparing mahya was a complex and laborious job requiring considerable skill. By means of boxwood rings, pulleys, hooks, ropes and other equipment, the many hundreds of lamps were arranged in different patterns from just after the Ramazan evening meal known as iftar until the end of the teravih prayers, a period of at most two hours. When Ramazan fell in winter, the mahyacı had to put up with bitter cold on the minaret balconies to display his skills, so it was a job only for dedicated enthusiasts. They spent the entire day preparing for that evening’s new display: first sketching the design on squared paper, then calculating the number of lamps needed and the positions of each lamp on the different ropes, which were then marked by knots. They rehearsed to check that all would go smoothly on the night, filled the lamps with olive oil, prepared wicks made of pistachio stems or baked reeds wound in cotton wool, and then placed the lamps into their round holders.

As the hour of iftar drew to an end, a mahyaci would climb up to the minaret balconies, light the lamps, and begin to let them out using pulleys until they were all in place and the composition complete. There was fierce rivalry between the mahyacıs of different mosques to produce the most impressive display, and each evening’s new design was a jealously guarded secret. Crowds would begin to gather as the first lamps were drawn into place and try to guess what the finished result was going to be: “I think it’s a paddle steamer!” Or, “It must be the wheel of a gun carriage!”

The larger mosques had special rooms where the paraphernalia of the mahya illuminations were kept; the job of mahyacı was passed down from father to son.

Although the custom of lighting lamps is common throughout the Islamic world, mahya illuminations are a tradition almost unique to Istanbul, for the simple reason that only mosques which had at least two minarets could be used. Royal mosques with two, four or six minarets are mainly located in Istanbul, although there are some in Edirne, the former Ottoman capital, and mahya illuminations were set up there as well. The oldest Edirne mahyacı whose name is remembered is Hacı Aliş Ağa (d.1668), who was known by the cognomen Mestî. He is said to have had poles erected in the Maritza River across which he prepared illuminations known as askı mahyası (suspended mahya).

Exactly when mahya illuminations began in Istanbul is uncertain, although one story attributes the custom to the reign of Ahmet I (1603-1617). As the story goes, one Hafız Kefevî, calligrapher and müezzin at Fatih Mosque presented an embroidered handkerchief to the sultan at the beginning of Ramazan. Ahmet I liked it so much that he ordered the design to be depicted in lamps hung between the minarets of his own Sultanahmet Mosque. Ahmet Rasim (1864-1932) quotes this story from an old manuscript, Menakıb-ı İslâm, and suggests that the word mahya might be derived from the Persian mahiye (of the moon) or müheyya (prepared, arranged in a row). Old authors record that Istanbul’s famous mahyacıs would embroider their new designs on red, green and blue satin and present them to the sultan, who would give his approval for the designs and reward each mahyacı.

Most impressive of all the mahya displays were undoubtedly the moving illuminations of Süleymaniye Mosque. One of these moving pictures consisted of boats and fish moving in front of a bridge, across which a carriage passed. When we remember that 122 lamps were required to represent a sailing ship and 198 a royal barge, these moving illuminations must have required far more.

On the Night of Power towards the end of Ramazan, it was customary to illuminate the minarets from the summit of the cone to the balcony with vertical rows of lamps, a display known as kaftan giydirmek (dressing in a kaftan).

An engraving in the travels of Salamon Schweigger, who visited Istanbul in 1578, depicts a mahya illumination on a rope stretched between the minarets of two [adjaceant] mosques. Clearly then, this custom predates the reign of Ahmet I. The 17th century Turkish writer Kâtip Çelebi writes that in 1523 Grand Vezir Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Paşa ordered mahya illuminations to be set up on the major mosques in the city.

Abdüllatif Efendi (d.1877) won renown one year with his depiction of a royal barge [hung] between the minarets of Süleymaniye Mosque on the fifteenth night of Ramazan . The same mahyacı was also called in for occasions other than Ramazan, and in 1867 wrote the words “Long live the Sultan” on the hillside behind Dolmabahçe Palace when Sultan Abdülaziz returned from his state visit to Europe. In similar fashion, he prepared an illumination between ship’s masts on the Bosphorus when the Khedive of Egypt, İsmail Paşa, arrived at his palace in Emirgan.

By tradition, the illuminations for the first fifteen days of Ramazan consisted of words, and those for last fifteen days of pictures. The writing was usually in the sülüs or celi styles of [Ottoman] script and consisted of one, two, or three words, the most common being ‘Welcome Celebrated Ramazan”, “May God Protect”, “Thanks be to God”, “Allah”, and so on. In 1911 non-religious slogans such as “Hurrah for Liberty”, “Assist Orphans”, “Do not Forget the Red Crescent”, “Remember Aircraft”, “Buy Local Goods”, “Long Live the National Pact”, and “Long Live Independence” came into fashion. The pictures usually included motifs from Istanbul life, such as Kızkulesi (the Maiden’s Tower), mosques, pavilions, bridges, caiques, sail-boats, stars and crescents, fountains, birds and roses.

Electric Mahya for Modern Turkey

Many late 19th and early 20th-century writers on life in Ottoman times have left accounts of mahya illuminations in their own childhoods. For example, Sermet Muhtar Alus recalls children waiting eagerly for the mahya pictures which began on the fifteenth of Ramazan and the pleasure they took in watching the paddle steamers, caiques, towers, swings, cradles, and other designs appear night after night.

By Nimet Berkok Toygar – Kâmil Toygar

One of the five pillars of Islam is to keep the fast during the month of Ramadan. As a religious observance, the fast is a particular time period during which people refrain from doing certain things. To put it another way, the fast is an act of devotion, observed by not eating or drinking from dawn to dusk and by refraining from sexual relations. It was instituted during the second year after the Prophet Muhammad’s flight from Medina.

Ottoman jam-makers

A significant portion of our culinary culture has developed around Ramadan and has to do with preparation for the month. In Ramadan of old when, unlike today, every sort of fruit, vegetable and dried goods were not found throughout the year, foods and ingredients that would be consumed during Ramadan were prepared or bought during the seasons when they were cheap and plentiful.

The foods that were bought or prepared ahead in large quantities and known as ramazanlık or ramazaniyelik were of special importance when Ramadan fell during the winter months. Some foods bought for Ramadan which indicate the richness of our cuisine include pastırma, sucuk, kavruma and other meat products, dried green beans, eggplant and red peppers, various pickles, cheese and oils, soup ingredients, especially tarhana, preserves, marmalades and fruit leathers, ingredients for compotes such as sour cherries, apricots, plums etc., bulgur, noodles, rice and pasta, tomato and pepper pastes, dried yufka and other breads.

An Istanbul Pickle Shop

It was important that such foods be bought or prepared in quantities sufficient to last at least a month. Ingredients such as flour, oil and sugar, which at other times were bought weekly or daily, would be bought in large bags or tins to last throughout Ramadan. In some areas, this is known as ramazan tedariki, or Ramadan procurement.

Abdülazız Bey, who provided important information about Istanbul life during the last century in his book Osmanlı Adet, Merasim ve Tabirleri (Ottoman Customs, Ceremonies and Expressions), describes the preparation for Ramadan thus:

Traditional Ottoman jam vessels

“In the sweet shops, samples of various preserves were laid out on small saucers, and were decked with sweets, ingredients for sherbets, and sherbet cups known as haması. Tobacconists chopped âlâ Boğça, Yenice and Samsun tobaccos and packaged them up in all manner of fine papers. All the neighborhood coffeehouses were swept, their windows were cleaned and the Karagöz (shadow play) performers and orta oyun theatre (a type of traditional Turkish theater) companies rented the large coffeehouses throughout Istanbul in which to perform their arts.

“[Shops stocked] spices to put into soups and incense to burn while the Holy Koran was read. Bottles, plugged with cotton, contained mustard to be eaten with the dish known as bumbar (stuffed intestine). There were dates to break the fast at iftar and all sorts of spiced candies. And outside the glass doors [of the shops, peddlars sold] all sorts of simit, çörek and Ramazan pide (special breads for Ramadan).”

Those who were well-off followed the custom of sending Ramadan provisions to relatives, friends and neighbors. Today’s custom of factory/business owners distributing ramazanlık to their employees can be considered an extension of that old custom.

As a result of Turkey’s many developments in agriculture, almost every fruit and vegetable is now available year ’round. We believe that because of this, the preparations for Ramadan will soon be left only as a nostalgic memory.

The meal eaten before the break of dawn (fecr-i sâdık) by those intent on keeping the fast is called sahur. Sahur, called the “blessed meal” by our Prophet, is the beginning of the day of fasting.

The eating of sahur by one who will fast is not a religious requirement but is recommended, as it will provide him or her strength throughout the day. Thus, the sahur meal is recommended in a Hadith (İbn Maja, Saum 22).

Our Prophet made a command to this effect in another hadith:

Eat the sahur, for in the sahur is a blessing. (2:495)

It is also recommended not to eat the sahur meal too early. But all eating and drinking must obviously be finished before dawn, as dawn marks the beginning of the fast.

As one will go back to sleep after sahur, the foods must be chosen with care. In addition to flavor and beauty in appearance, it is absolutely necessary that sahur foods be healthy. The chief point to be considered is that the foods not be too heavy or rich, but last us until iftar, the breaking of the fast. Making sure that sahur foods are not too salty will help prevent us from becoming thirsty during the day.

Writer Münevver Alp provides much information about Ramadan in old İstanbul:

“In Anatolia and Rumelia, the staples of the sahur meal were gözleme and börek. The women would knead the dough at night, and bring the gözleme and börek to the table freshly baked. In Istanbul, however, börek was not eaten for sahur; the sahur table contained kazandibi, çöreks, kashkaval cheese, neck meat and cold sliced tongue.

Gozleme on a griddle

“One evening there would be pilav, the next evening a type of noodle called taygan. Everyone would eat a bowl of yogurt and a bowl of noodles or rice. Then, before washing their mouths and declaring their intention to fast, they would have a bowl of compote and say “yarrabi sana şükürler olsun” (Oh, my Lord, thanks be to you) and declare the intent to fast that day. After declaring their intent, they would read the Koran until the morning call to prayer, perform namaz, and then go back to bed, sleeping till noon.”

Among the [contemporary] families we interviewed, the foods eaten today for sahur mostly consist of leftovers from the previous evening’s iftar. The first food at sahur would be a meat and vegetable dish, followed by noodles or pilav. Börek is also notable for its ability to keep one satisfied. The most common drinks are ayran, fruit drinks, tea, and compotes.

Haci Bekir, a renowned Istanbul candy shop

The Feast of Ramadan, Eid-ul-Fitr, or as it is known in Turkish, Şeker Bayramı, the “Sugar” or “Candy” Feast, is an expression of the joy at having fasted for the month of Ramadan and having gained God’s favor. At the same time, it is the anniversary of the second observance of Ramadan after the flight to Medina, during which the Prophet with his small army met the Quraishi army, many times stronger than his own, and soundly defeated them. When the Prophet returned to Medina following this battle, the month of Ramadan had come to its end, and the fast was over. In a speech to his followers, he told them to perform a special prayer (namaz) on the first day of Shawwal, which followed Ramadan, and to give a certain percentage of their goods to the poor. The first Feast’s prayers, namaz, were performed on that date.

Encompassing the goals of reconciling those in conflict while strengthening feelings of friendship and family, the Feast or Ramadan is also important as it relates to our culinary culture.

In the Ottoman Empire, the official celebration of Ramadan began during the 15th-century reign of the great sultan Mehmet the Conqueror. The scholar Feridun Fazıl Tülbentçi describes the ceremony in the palace:

“The Feast was of great importance within the Ottoman palace and to the Sultanate. In the palace, the religious holidays Iyd-i Fıtır (Eid al-Fitr, Feast of Ramadan) and Kurban Bayramı (Feast of the Sacrifice) were second only to an accession to the throne. A ceremony began two days prior to the Feast, in the second courtyard of the palace, known as the Alay Meydanı (Procession Square). The ceremony was known as the Arife Divanı or Arife Muayedesi. The Mehter band played, prayers were recited, and praise was given. As part of the protocol of the Feast, the Sultan received felicitations. The ceremony was carried out with such precision that if, in a later Arife Muayedesi the Sultan himself did not emerge, the ceremony was held across from the throne with a turban placed upon it. (Sultan Ahmet II did not emerge as he had pains in his feet, so he had the ceremony conducted before his turban.)

Bayram at Topkapı Palace, 1789

“On the first day of the Feast, the ceremony became more ostentatious. During the evening of the Feast, from midnight on, the outer gate of the palace was opened, and those who would participate in the felicitations would begin to arrive. When morning came, the Şeyhülislam and later, the Grand Vizier would come as well. The ceremony was quite long; the Mehter band played and cannons were fired. At the close of the greeting ceremony, the sultan would go with a great procession to Haghia Sophia or Sultan Ahmet Mosque and perform ritual prayers for the Feast.”

Common people also prepared with great excitement for the Feast of Ramadan. Their shopping began in the second half of the month; in particular, shoes, clothes, and undergarments were bought for the children, who were dressed anew from head to toe. The children of close relatives and friends were not forgotten.

Especially following Kadir Gecesi (The Night of Power), the markets and bazaars were filled to overflowing, with the candy shops conducting the most business during the Feast, as all guests to private homes were offered candy.

Sesame-covered simit remain popular in Turkey

In public celebration areas, itinerant old hajjis would sell sweets, sherbets, çörek and simit to the people.

As mentioned earlier, the most distinctive of the Feast’s treats were the candies and other sweets offered to visitors. Among these were home-baked pastries, the most common of which were baklava, kadayıf, hurma tatlısı, etc.

Along with sweets, chicken soup, rice pilav with meat, and various types of börek were specially made for the holiday.

This translation of an original article by Nimet Berkok Toygar and Kâmil Toygar, Ramazan Yemekleri ve Mutfak Kültürü, Volkan Matbaacılık; Ankara,1996, is reprinted courtesy of The Turkish Cultural Foundation.