apple, what might you not have done for a truffled turkey?”

In the late 18th century, shortly after the founding of the United States of America, the statesman Benjamin Franklin wrote to his daughter:

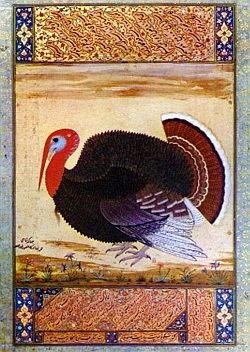

“I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the Representative of the Country; he is a Bird of bad moral Character, like those among Men who live by Sharping and Robbing, he is generally poor and often very lousy…The Turkey is a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America.” (1)

No stranger to the pleasures of the table, Ben Franklin was doubtless well acquainted with the wild turkey, a game bird indigenous to North and Central America.

In considering these birds, I would like, first of all, to deal with the English noun “turkey.” Unabashedly, I confess it to be my inspiration for this paper, which I first delivered in the country of the same name.

The most convincing etymological sources (2) speak of fowl known as “turkey cocks” in reference to large domesticated birds (probably of the genus Pavo). By mid-16th century “Guinea hens” were synonymous with “turkey-cocks” and referred to fowl of African origin. Some of these were supposed to have been brought from West Africa (Guinea) and others from Numidia via the Turkish dominions, hence the name “turkey.” Sixteenth century Spanish explorers in Mexico found that the Aztecs had domesticated a large fan-tailed bird, the huexolotl, which was prized for its meat and regularly offered as tribute to the Aztec monarch, Montezuma. The Spaniards introduced this bird to Europe, where the confusion over its name began.

For those of you who like to know the origins of words you eat, here is a brief summary of what happened to the feathered pride of the Aztecs:

The Spaniards called the new bird pavo, after the European fowls they knew.The French, considering the bird to be from the general Caribbean region, called the creature poule d’Indes, or dinde, after the Caribbean islands Columbus had mistaken for India, now known as the West Indies. Later, in provincial areas of France, the birds were sometimes known as jusites after Jesuit brothers who started a turkey farm near Bourges. (3)

Linnaeus, the great Swedish classifier, mistakenly gave the New World creature the Latin name that rightfully belonged to the Old World fowl, Meleagris gallopavo. Thus, something else (Numida meleagris) had to be concocted for the turkey-cock. (Meleagris means speckled.) (4)

The English called it turkey because it was closer in appearance to their turkey-cocks that to anything else they’d seen. The Turks, probably to agree with the French, or maybe because they thought it inappropriate to roast a creature named for their nation, chose to call the bird hindi, thus pushing matters farther east.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese preferred to go west. Sources mention that they wrongly supposed the bird to have come from Peru. To this day, Portuguese speakers from Brazil to Goa call the bird peru. And thanks to Portuguese trade with India, the Hindi name for turkey is piru.

The Arabs took their own word for cockerel, dik, and added the Arabic adjective pertaining to Turkey or Asia Minor, rumi, which referred back to the Byzantine Empire, of the Land of Rome. Thus, dik rumi, an Arab turkey, is really a Roman rooster.

But it is none other than the wild Meleagris gallopavo that American folklore has solidly established itself as one of the native foods enjoyed by the Puritan colonists of Massachusetts when they celebrated their first Thanksgiving in 1621. That feast was, by all accounts, a prayerful occasion during which the English pilgrims thanked their Savior for a safe flight from religious persecution in England and for the bounty of their first harvest in the New World.

To properly appreciate turkey’s place within the cuisine of the United States, one must look briefly at the development of our holiday commemorating the Pilgrims. As a feast-day, it was not an instant success. After that initial Pilgrim banquet, over two centuries would pass before Thanksgiving, the most “typically American” of celebrations, was officially decreed a national holiday.

Beginning in the 1820’s, Mrs. Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of an influential women’s magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book, carried on a patriotic crusade for the establishment of Thanksgiving as a national holiday. She wrote hundreds of editorials and letters urging politicians, clergymen and the readers of her periodical to lobby for this cause. Finally, in 1863 in the midst of the American Civil War and shortly after the Northern Army’s victory at Gettysburg, the combination of Mrs. Hale’s annual exhortations and the Northern desire to celebrate its triumph prompted President Lincoln to proclaim the third Thursday in November as the national day of Thanksgiving. As early as 1857, Mrs. Hale filled the cookery pages of the November issue of Godey’s with recipes for roast turkey and other dishes to be served at the Thanksgiving meal. Despite myriad changes in food technology, taste, and society since then, American magazine and newspaper food editors still adhere to Mrs. Hale’s basic format.

Mrs. Hale and President Lincoln may have assured the seasonal demand for turkey, but so plentiful were the wild turkeys that turkey breeding for superior flesh did not attract significant commercial interest until the 20th century. Earlier American turkey breeders had concentrated on the production of large feathers deemed essential for Victorian womens’ hats and fans. (5)

While the fashion for turkey plumes may have subsided, the cooking of turkeys continued to be a subject of much discussion and divergent opinion. In “Statesmen’s Dishes and How to Cook Them” (1890), Mrs. Stephen J. Field suggested that “three days before [a turkey] is slaughtered, it should have an English walnut forced down its throat three times a day and a glass of sherry once a day. The meat will be deliciously tender and have a fine nutty flavor.” (6) An eighteenth century adventurer in the American Midwest extolled the merits of stewing a turkey in racoon fat. (7)

Currently, one highly successful processor of oven-ready turkeys advertises birds that are “self-basting.” Its raw turkeys are injected with corn oil to keep the meat from becoming too dry. Many of these turkeys are also equipped with heat-sensitive devices that indicate precisely when the bird is done to perfection.

Though its stuffings of bread-crumbs and herbs, nuts and dried fruits, sausage meat or oysters vary widely from kitchen to kitchen, a roast turkey is an essentially simple affair. It is no surprise that in the American idiom, “to talk turkey” means to speak plainly and directly, to deal with the basics. Hence one well-known firm’s “Turkey-Talk Line,” a toll-free telephone assistance service which operates from a few weeks before Thanksgiving through the Christmas-New Year holidays. Despite innovations such as birds with embedded thermometers, the firm receives thousands of calls from distraught, once-a-year turkey chefs who prove that “fool-proof” is a relative term. Panic frequently arises when a consumer has neglected to remove the bird’s plastic wrapping before placing it in the oven or has forgotten to turn the oven on until half an hour before dinner is to be served to a dozen guests.

Sentiments about Thanksgiving are strong. And since a superabundance of family members and food are what characterize the celebration for most Americans, it is not surprising that there is a collective attachment to family food traditions. This tends to discourage avant-garde experimentation. Turkeys stuffed with couscous or accompanied by a kiwi chutney do appear in magazines, but by and large, most Americans cooking for their families are unlikely to tamper with tradition at Thanksgiving. Though few would dispute the festiveness of a fine rack of lamb or a magnificent bouillabaisse, few Americans would seriously consider either suitable Thanksgiving fare. (8)

By virtue of its iconic role in the Thanksgiving dinner, turkey has become an American symbol—not so much to non-Americans, who may associate the United States with beef cattle, great grain fields, and fast food—but by Americans themselves.

Unofficially, at least, the bird with the ugly head and the spectacular plumage eventually achieved some of the status Ben Franklin begrudged the eagle. During World War II, extraordinary measures were taken to ensure that American troops overseas, and even those fighting on the front lines, were given hot turkey dinners on Thanksgiving Day. (9) & (10)

Oddly, mass popularity has not diminished wealthy or fad-following Americans’ appetite for turkey. It continues to be a meat for feasts even as improved farming has made it plentiful and cheap enough to be used instead of beef or pork scraps in sausages and hot dogs. And lean, freshly ground turkey, sold alongside ground beef in supermarkets the year round, carries no message of either Pilgrim piety or holiday largesse. More often than not, it is simply labeled “low-cholesterol.”

Despite advertising’s transformation of turkey into an inexpensive “health food,” a browned, well-basted roast turkey is in no danger of being supplanted as the centerpiece of our holiday devoted to unabashed gluttony. But what irony that the turkey (albeit stripped of its flavorful, fattening skin) should also epitomize prudent restraint for body-conscious Americans today. What would the Pilgrims think?

— Holly Chase

Notes & Bibliography

(1) The American Heritage Cookbook and Illustrated History of American

Eating and Drinking, American Heritage Publishing Co., 1964; p. 482.

(2) The Oxford English Dictionary, second edition.

(3) Larousse Gastronomique (English edition), Crown Publishers, New

York, 1964.

(4) The Oxford English Dictionary.

(5) The Thansgiving Book, by Lucille Recht Penner (Hastings House, New

York, 1996), p. 115.

(6) See note 1, p. 483

(7) The Wild Turkey: Its History & Domestication, by A.W. Schorger

(University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla; 1966, pp. 370-1). An

entertaining blend of exhaustive research and superior writing– food

scholarship at its zenith.

(8) When “new” dishes enter the Thanksgiving repertoire, food writers tend to link them to earlier American traditions. And America, at least in the geographical sense, certainly includes Mexico, source of the turkey. Yet I know of no proposals to add two especially splendid Mexican turkey recipes to the Thanksgiving table.

The first Spaniards in Mexico wrote that the Aztecs ate turkey with a sauce based on bitter chocolate, the ancestor of today’s mole poblano, a seductive poultry sauce from the Mexican state of Puebla. And then there is pavo en escabeche, stewed turkey marinated in oil, vinegar, herbs and onions—a dish with obvious Mediterranean antecedents.

(9) Thanksgiving: An American Holiday, An American History, by Diana Karter Applebaum (Facts on File Publications, New York and Bicester, England, 1985); pp. 249-250.

(10) The most typical “trimmings” would include a sage and bread stuffing, mashed potatoes, giblet gravy, cranberry relish, creamed onions and fresh celery.